When

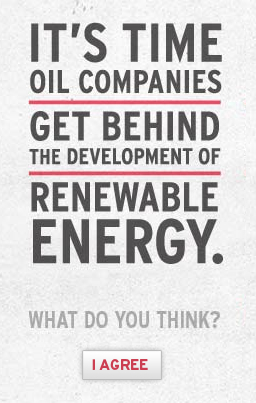

I first saw Chevron's new full-page newspaper ads last week, I thought

they were a joke: a series of big pictures of happy people supported

with minimalist text claimed that the company "agreed" on issues like

clean energy and community involvement, without ever revealing with whom

it agreed nor acknowledging that its claims conflicted with its

corporate behavior.

When

I first saw Chevron's new full-page newspaper ads last week, I thought

they were a joke: a series of big pictures of happy people supported

with minimalist text claimed that the company "agreed" on issues like

clean energy and community involvement, without ever revealing with whom

it agreed nor acknowledging that its claims conflicted with its

corporate behavior.

So a culture-jamming group called the Yes Men did it for them, distributing a press release and running a website with information about Chevron's various environmental sins and turning the campaign into a real conversation-starter. The media dubbed it a "hoax" even though, unlike Chevron's meticulously worded propaganda, it spoke the truth.

"We expected something like this would be done," said a Chevron spokesman, "[because] there are activist groups whose sole focus is attacking Chevron and not engaging in rational conversations on energy issues."

One of the more insidious qualities of communicating in our networked world is that you can assert truth if you lie consistently and enough, but only sort of. Secrets are increasingly difficult to keep and reality might be somewhat subjectively determined but it is a naggingly inescapable lodestone. These facts make Chevron's campaign and response utterly dishonest, and here's why:

- If they 'expected something like this,' they wouldn't have created the campaign. Chevron did exactly what BP did for over a decade, sending its advertising experts to find little pearls of good news that could be blown out of proportion to substantiate claims that weren't contextually true. The company no more "agrees" with anybody other than its supporters than BP had any intention of remaking the operations of a company "beyond petroleum." Duh.

- If the Yes Men hadn't propagated the information, it was still readily available. The campaign begs the question of who Chevron was trying to influence. The people who truly question its behavior know full well its context from any number of existing websites and online groups, so their disdain of the ads would have been easy to predict. As for the consumers who were unaware of the negatives there's a good case to be made that they wouldn’t pay attention to (or care about vis a vis any future behavior) the positive spin on the ads.

- You can't call propaganda a "conversation" and not expect to start a real conversation. If Chevron actually intended to talk with, and not at its critics and consumers alike, it could have run ads that posed thorny questions and then solicited real, meaningful input. It could have promised to strive for consensus and then to take action, perhaps committing budget a priori to any conclusions. Instead, it chose to run ads that begged to be challenged and then were, thereby giving it the conversation it claimed to desire...if not exactly the one it wanted.

It begs the question of the ultimate point of the exercise.

Chevron, like all oil companies, is on the wrong side of really important issues. It exploits the planet's irreplaceable resources, despoils the environments and communities in which it finds the stuff, and directly contributes to geopolitical unrest. The flip side, however, is equally enormous: its products power and help build how we get around, what we wear and use, and the financial well-being of hundreds of thousands of people.

So why act as if readers live in an information vacuum or, worse, that they can be lied to?

I have long believed that the real challenge for oil companies is to tell people the truth about the industry. This would necessitate abandoning all the schmarty-pants creative excuses and work-arounds, and address the incredibly difficult and complicated qualities of our ongoing love affair with oil. Demand more of consumers by treating them like adults. I don't know how to do this, though. It's a giant challenge, and maybe that's why all of the companies opt for avoiding it.

Thank goodness the Yes Men held Chevron accountable this time. Consumers should, too.

(Image credit: a graphic resembling one of the ads from the campaign, from Chevron's website)

So a culture-jamming group called the Yes Men did it for them, distributing a press release and running a website with information about Chevron's various environmental sins and turning the campaign into a real conversation-starter. The media dubbed it a "hoax" even though, unlike Chevron's meticulously worded propaganda, it spoke the truth.

"We expected something like this would be done," said a Chevron spokesman, "[because] there are activist groups whose sole focus is attacking Chevron and not engaging in rational conversations on energy issues."

One of the more insidious qualities of communicating in our networked world is that you can assert truth if you lie consistently and enough, but only sort of. Secrets are increasingly difficult to keep and reality might be somewhat subjectively determined but it is a naggingly inescapable lodestone. These facts make Chevron's campaign and response utterly dishonest, and here's why:

It begs the question of the ultimate point of the exercise.

Chevron, like all oil companies, is on the wrong side of really important issues. It exploits the planet's irreplaceable resources, despoils the environments and communities in which it finds the stuff, and directly contributes to geopolitical unrest. The flip side, however, is equally enormous: its products power and help build how we get around, what we wear and use, and the financial well-being of hundreds of thousands of people.

So why act as if readers live in an information vacuum or, worse, that they can be lied to?

I have long believed that the real challenge for oil companies is to tell people the truth about the industry. This would necessitate abandoning all the schmarty-pants creative excuses and work-arounds, and address the incredibly difficult and complicated qualities of our ongoing love affair with oil. Demand more of consumers by treating them like adults. I don't know how to do this, though. It's a giant challenge, and maybe that's why all of the companies opt for avoiding it.

Thank goodness the Yes Men held Chevron accountable this time. Consumers should, too.

(Image credit: a graphic resembling one of the ads from the campaign, from Chevron's website)