On Monday, Oct. 18, at 2:04 a.m, I received an email from Chevron Investor Relations. I wasn't awake then, but at 6:15 a.m. or so, I read the release. The claim--that Chevron was taking direct responsibility for the mistakes they have made and included quotes like this one: "For decades, oil companies like ours have worked in disadvantaged areas, influencing policy in order to do there what we can't do at home. It's time this changed."

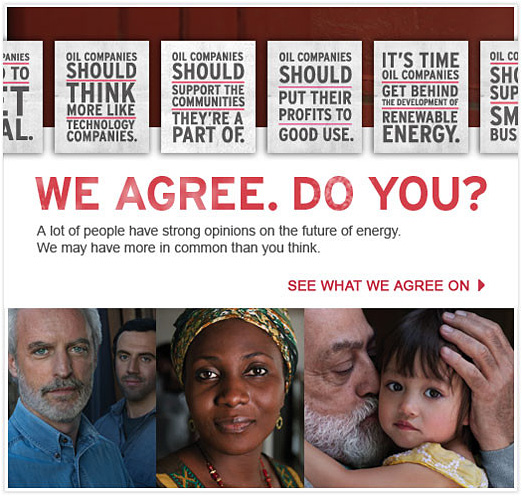

Such candid transparency seemed too good to be true. And, as many readers probably know by now, it was. I realized after looking through the release's links that, while the design of the press room they mentioned quite closely mimicked the Chevron site and linked back to various Chevron sites, the URL was a bit different. Further, I went to the actual Chevron corporate site and looked at their press room. Turns out, Chevron was kicking off a campaign that the fake site closely mirrored, but the existence of a much less risky "We Agree" campaign on what seemed to be the legitimate corporate site for Chevron assured me that a hoax was at play.

At the time, not many reports had been filed about the middle-of-the-night email. A couple of sites had already picked up on it as legitimate news. I emailed the example around to the team at Peppercom and went on about my day. And, ever since, the news has really exploded about the stunt, revealed to be the latest project of the controversial Yes Men.

The Yes Men have a long history of pulling stunts that dupe people as a way of drawing attention to a legitimate event. In the U.K., they purported that Dow Chemical was going to pay reparations totaling $12 billion for the chemical disaster in Bhopal by posing as a spokesperson from Dow on the BBC, sending Dow stocks down tremendously. In the U.S., hoaxes have included staging a press conference from the Chamber of Commerce and claiming to have reversed the Chamber's policy on climate change, as well as posing as HUD to announce that housing projects which were sitting vacant would be re-opened in New Orleans.

Not surprisingly, many initially picked up on the hoax. Even Fast Company initially reported the Yes Men press release as legitimate--and later issued a mea culpa, with credit given to the elaborate lengths The Yes Men went to. I had a chance to get some comments on the hoax from Dave Samson, General Manager of Public Affairs for Chevron. Samson said, "In reality, I believe these pranks only serve to marginalize those groups who engage in such deceptive behaviors."

Yet, hoaxes have a deep history in our culture. Back in August, I wrote a piece about our fascination with figures like P.T. Barnum, Andy Kaufman, and World Wrestling Entertainment's Vince McMahon who constantly blur the distinction between fantasy and reality. The WWE has been known for having Vince McMahon the character die on screen, only to issue a "legitimate" press release to further purport McMahon's demise. Back in 1835, The New York Sun ran a series of articles from a purported scientific study which had discovered life on the moon. While, as the series went on, it became obvious to many readers it was a work of fiction, the Sun never openly admitted that the story was not legitimate.

Another hoax of this sort happened last year in the U.K., after Tory MP Chris Grayling made a comment comparing Moss Side in Manchester to the Baltimore depicted in The Wire. A blogger named Alex Hilton decided to "produce" a response from the Baltimore Mayor Sheila Dixon, creating a replica of the mayor's site and ultimately getting "her" comments picked up by The Guardian in the U.K. and The Baltimore City Paper.

I'm fascinated by these sorts of performances and firmly believe they play a crucial role in our society. Not only might they bring major issues to public consciousness in the sort of way that will make people talk to them, but they also serve as a constant warning not to take any report we read at face value, to always be questioning. By demonstrating that journalists are human beings that can be duped as well, these elaborate stunts encourage readers to be more discerning and journalists to double-check sources. In a digital era where a much wider portion of our citizens have access to publishing tools, these sorts of performances will become increasingly commonplace, as it puts publishing tools in the hands of activist groups who would not have had them before while also playing to our longstanding love of roleplaying and tricking one another.

However, while these hoaxes can drive public attention to crucial issues, I am concerned when "regular" non-profit organizations get involved. Just as politicians rail on "the system" when running for office only to become much less productive once they are part of it because it's hard to get their colleagues to work with them, NGOs/advocacy groups have to be careful at what cost they receive their attention, especially if progress ultimately requires the groups to sit down together. That working relationship might be damaged considerably if a company feels an attack on them was "unfair." In the case of Chevron, accusations of "greenwashing" from the outside might feel like steps of realistic progress on the inside.

Samson said about the "We Agree" ads, "The campaign is designed to identify and highlight common ground on key energy issues, so we can move forward in a collaborative and intelligent way. Most businesses know they will always have their critics, but I think many companies would choose to engage with people who see benefit in having a meaningful dialogue versus those who simply resort to worn-out rhetoric and stunts."

Obviously, groups like The Yes Men feel that the "deceptions" of their actions pale in comparison to the "deceptions" they perceive from the corporations they are impersonating, and they have expressed just that sentiment many times in the past. NGOs seeking to advocate for change within industries, however, cannot afford to take such an antagonistic approach and actually hope to work with people at those companies to ultimately make tangible progress toward change. In short, in my mind, we gain a lot from groups like The Yes Men who get the attention of the greater public directed toward issues they should pay deeper attention to. However, perhaps even more important is having parties dedicated to evolution and making change happen in the incremental steps it always takes, perhaps benefiting from the efforts of these "revolutionary" moves from groups like the Yes Men while offering to work with companies on a concrete way to move forward.